Diego Augusto Ferreira had borrowed a neighbor’s motorcycle on a Saturday evening in Rio’s west zone. The 25-year-old, who worked as a street hawker in downtown Rio, was on his way to buy oil for his grandfather’s car.

But he didn’t return. Instead, a bullet to the neck on May 12 turned him into the first civilian to be definitively killed by army personnel in Rio de Janeiro’s federal intervention. “The city is getting more and more violent… we leave home and don’t know if we’re coming back, what we’ll find in front of us,” read one comment online following Ferreira’s death.

When Brazilian President Michel Temer announced that he would place national armed forces in Rio to combat rising crime rates, many understood it to be a precursor to a presidential campaign. But even as it began, the National Council for Human Rights called the measure “a license to kill”, and said that it legitimized “war ideology as a justification for eventual civilian deaths.”

President Temer announced that the military would be presiding over a federal intervention in Rio de Janeiro in the days following Carnival, and signed the decree on February 16. The idea was criticized from its conception, with analysts, human rights organizations and members of the public commenting that it lacked both short- and long-term strategy. Additionally, the initiative’s projected costs came to BRL 3.1 billion.

After two months, research shows that Rio’s levels of violence, crime rates, and public feelings of insecurity have only increased since the intervention began. At present, three months into the intervention, violent crime is still taking place with alarming frequency – leading experts and residents to conclude that the intervention is failing. And despite the idea’s initial approval, it hasn’t helped Temer’s chances.

Increased violence

The number of shootouts in Rio increased by 15.6 percent in the intervention’s first two months compared to the two months prior, according to Fogo Cruzado, an app which tracks gunshots in real time across Rio. The day before the intervention’s two-month anniversary, a stray bullet traveled through a school wall and killed a baby – the fifteenth child death due to stray bullets in 2018 alone.

“After three months of federal intervention, the analysis of indicators from different sources reveals that the violence continues at very worrying levels,” said Silvia Ramos, one of the coordinators of the Intervention Observatory, a research effort to track the intervention’s impacts in Rio.

“The intervention’s command did not make the promised changes and, on the contrary, some historical patterns of Rio’s security policies have worsened, such as the maintenance of violent police operations, violations of the rights favela residents, and corruption,” she continued.

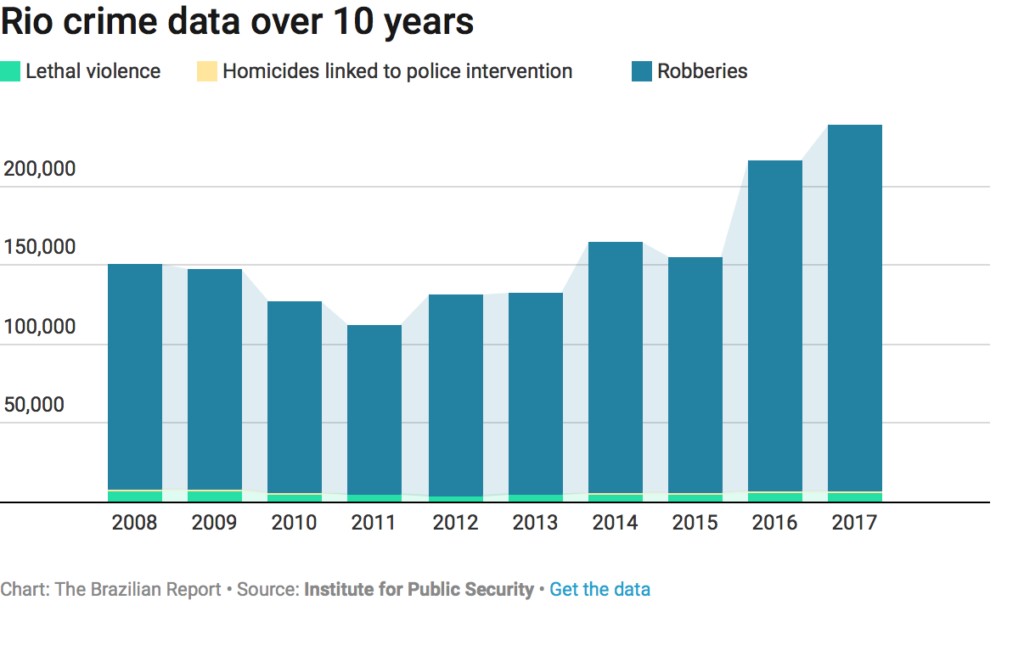

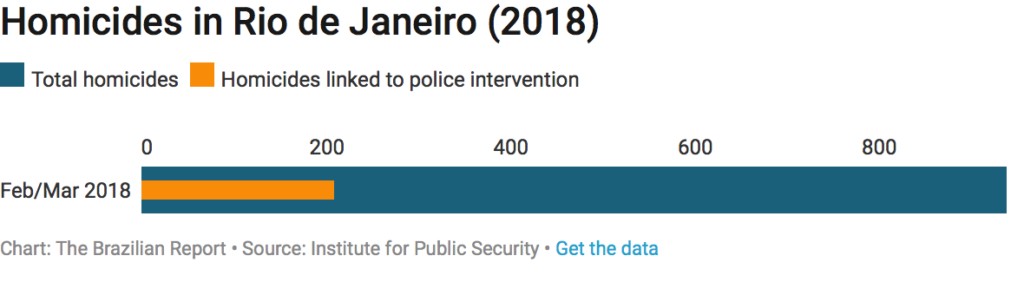

Newly-released crime data from Rio’s Institute for Public Security (ISP) shows that the intervention’s efforts in combatting crime have been minimal, with minor variations compared to the same period in 2017. The intervention’s spokesperson Roberto Itamar said, via live internet transmission on May 18, that results would take time.

The Observatory’s results show that despite Brazil’s track record of using military force to control extreme outbreaks of violence – as was the case with Vitória, Espírito Santo in April 2017 – it is incapable of resolving the structural problems which create that violence in the first place.

Rio’s levels of violent crime remained similar to elsewhere in Brazil, while 37 percent of the population living in favelas and 30 percent living in the formal city said they had been caught in a crossfire between police and criminals since the beginning of the intervention. Furthermore, 92 percent of respondents in the Observatory’s research said they were afraid of finding themselves in the middle of the crossfire.

Favelas are suffering the worst consequences, with routine operations adding to the city’s already-high civilian death toll. Most deaths – like that of Matheus Mello, a 23-year-old shot on his way back from an evening Evangelical prayer service, the deaths of five young men in Maricá and the recent operation in Rocinha favela that killed eight – occurred far from the city’s affluent South Zone.

“[The intervention] has left a type of police officer who commits lawlessness acting freely, executing alleged criminals, robbing favelas and disrespecting all resident – as if favela dwellers were criminals,” Ramos told The Brazilian Report. “It’s been a long time since we’ve seen this sort of police officer acting so freely.”

But in addition to creating greater public fear and increasing violence against favela residents, the intervention is being heavily criticized for not meeting its aims. Drug traffickers have stated that they intend to continue running their operations as normal, and are simply doing so a little more covertly while the military is present.

Political motivations

“Political interests of the central government motivated the decree of the federal intervention,” said Ramos. “The decision was politically strong and allowed the government to abandon its main agenda, the pension reform, without [incurring] major damage. The measure aimed to strengthen the Temer government, both in the country and in the state, where the president’s party faces a deep crisis.”

The Observatory’s research concludes that the intervention’s hurried implementation and lack of planning, resources, or methods leave it in a state of constant improvisation. In addition to not solving Rio’s security crisis, the intervention also creates new dilemmas for the state: namely, its finances, a precedent for military interference in civilian institutions and an articulation of the idea that Rio’s security requires the same force as war.

“Only desperation or political opportunism can explain the decision to formalize, as a federal constitutional intervention, the military presence in public safety in Rio de Janeiro at this time,” said Frederico de Almeida, a political scientist at Unicamp, in a recent op-ed. “The presentation of a solution of force to a society frightened by violence can politically compensate for a government that is worn, illegitimate, and that cannot do what it was supposed to do.”

But the military’s new presence in various levels of government, including Michel Temer’s federal cabinet, is just one way in which the Brazilian army is angling for more political power. In March, 48 military personnel had already announced that they would be running for office in October’s elections, eyeing seats at all levels of government.

Although giving the military heightened powers within his administration plays out wellamong Brazilians desperate for a resolution Rio’s difficult public security scenario, research and analyses alike point to the conclusion that the intervention sets a dangerous precedent. “What will the federal government do if new situations of urban unrest occur in other parts of the country or if the situation in Rio is aggravated?” said Ramos.

“Will they issue a state of emergency? A state of siege? There were other appropriate solutions to Rio’s security crisis.”