On June 30, a baby was shot in his mother’s belly in Rio de Janeiro. After the rifle fire hit 29-year-old Claudinéia in the hip in the Favela do Lixão neighbourhood, her son Arthur was delivered via emergency cesarean section. He will be a paraplegic for life.

This was just one of 181 shootings that took place in Rio that June week. A day earlier, Marlene Maria da Conceição, age 72, was shot in the Mangueira favela while picking up her grandson from school. Her daughter, Ana Cristina, 49, was struck when she tried to help her mother. Both women died.

Just hours before her death, Ana Cristina had called the violence in her neighbourhood “unbelievable” on social media, posting that the “shooting has been going on for nearly three hours.”

Two days earlier, Fabio, a doorman returning home from work, was killed by shrapnel from a grenade at the entrance to the Pavão-Pavãozinho favela, a stone’s throw from Ipanema and Copacabana, two of Rio’s wealthiest neighbourhoods.

Even in Brazil, where homicides are all too common, Rio de Janeiro’s crime rate is stunning. It is now impossible not to notice that the city’s Police Pacification Units (UPP), once a much-vaunted anti-violence force, have all but collapsed.

Rio de Janeiro residents killed or injured by stray bullets every two days – 95% of those in favelas #Brazil https://t.co/Y3zCD4RvrP

— Shasta Darlington (@ShastaCNN) 16 de maio de 2017

Community policing

Launched nine years ago, the UPP program stationed some 9,500 officers in some 37 favelas, serving nearly 780,000 people.

This new model, which included components of successful community policing initiatives in Los Angeles and Medellin sought to end violent confrontations between rival gangs, and between police and gangs, by getting weapons out of the favelas and maintaining a permanent police presence.

At first, the media and the public loved the program. Rio saw a significant reduction in robberies in UPP-covered areas and a marked decrease in police killings, which fell from 1,330 in 2007 to 415 in 2013.

Some favela activists and human rights advocates viewed the UPPs as military occupation of low-income neighbourhoods, and predicted that the plan would fail. But the UPPs worked, or seemed to be working, keeping many areas of the city nearly free of shootouts, stray bullets and police killings from 2009 to 2013.

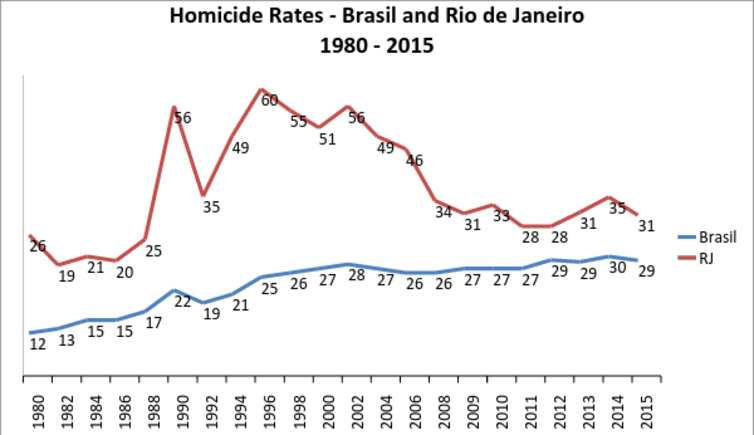

Rio’s homicide rate dropped significantly with the UPPs but then began a slow but steady rise.

The bad old days

This was a significant improvement over prior policing strategies in Rio. For two decades, the Rio police had one mission – to weed out the armed groups that had set up shop in all of the city’s 700 favelas – and one method to do it with – firepower.

By the late 1980s, gangs had essentially established territorial control over 1.5 Rio million residents, some 22% of the city’s population. Criminal groups such as the Red Command and The Third Command monopolised not only the drug trade in these areas but also other lucrative activities, such as cooking-fuel sales and alternative public transport.

The groups, which are operating again today, patrolled the streets and alleyways of Rio’s favelas, keeping both police and rival gangs out.

In 1995, the Rio de Janeiro state government hired an army general to try to control crime in the metropolitan region, and the city launched a series of public security policies meant to aggressively confront gangs in some of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods, not with investigation or intelligence but with guns.

‘Elite Squad’, a 2008 film about policing Rio’s most violent favelas in the 1990s.

xx

In short, it has been the war on drugs gone local.

Rather than fix the problem, research shows that these programs were largely responsible for more firmly rooting gangs in these places.

The demise of the UPPs

The UPPs were supposed to change all this, and for a while there they did. So what happened?

Based on studies done by the Centre for Studies on Public Security and Citizenship at Brazil’s Candido Mendes University, it appears that, over time, police officers in favelas have gradually reduced the practice of community policing and become more repressive.

The program’s decline happened gradually but, in retrospect, the 2013 disappearance of bricklayer Amarildo de Souza while in UPP custody in Rocinha, the largest favela in Rio’s wealthy south side, was an inflection point.

Tension between the police and residents rose across the city, but the police did not respond by updating program’s strategies, investing in training or renewing the force’s commitment to keep community policing at the heart of the UPPs.

By 2015, armed gangs had returned to once-pacified favelas such as Morro do Borel in swanky Tijuca, Morro dos Prazeres in bohemian Santa Teresa, and Favela Tabajaras in upscale Copacabana. The UPPs were faltering.

Any remaining vestiges of the mirage of safety crumbled once the Olympics ended, with skirmishes erupting between rival factions or Rio’s gangs – a “signal” for the groups to again take up heavy weaponry.

A Police Pacification Unit in Santa Marta favela in Rio de Janeiro, in 2013. dany13/flickr, CC BY

License to kill

The military police find themselves cornered in the favelas.

The force’s historic disregard for intelligence has come back to haunt it. Lacking sound information and data, young captains are forced to rely on their intuition to deal with the encroaching gangs, choosing between either daily shootouts or a hostile coexistence between gangs and police, depending on the favela.

Feeling stuck, angry and lost, police shoot frequently. At least 480 Rio de Janeiro citizens were killed by police in the first five months of this year alone.

The animation below by Amnesty International’s Fogo Cruzado (Crossfire) app documents all the gunfire in Rio from January to June 2017 – an average of 14 incidents daily.

RJ teve tiroteio todo dia de janeiro a junho, com média de 14 alertas diários. Mapa produzido pela equipe do @G1Rio pic.twitter.com/yIKo3VvMQ0

— Fogo Cruzado (@fogocruzadoapp) 10 de julho de 2017

The license to kill any favela resident perceived to be a criminal has given way to summary executions, which last year represented some 20% of all deaths in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Cops also kidnap suspects, take bribes to overlook crimes and negotiate to save the lives of criminals, exacerbating violence.

In fairness, things aren’t great for the police right now. Brazil is immersed in a profound economic crisis, so the police haven’t been paid in months. The force can’t even afford to fill its police cruisers with gas.

Rio’s police kill and die more than any other force in Brazil. Author provided

xx

Operating in dangerous neighbourhoods with little support or guidance from their commanders, UPP officers have reverted to the bad old days of excessive force and full-blown corruption.

The gangs, meanwhile, are following suit: they’re heavily armed, ambitious and bellicose. From January to June 2017, 81 Rio officers were killed (15 while on duty). Rio de Janeiro’s police kill and die more than any other Brazilian police force.

Amid these hellish conditions, young people in the favelas are starting to speak out. Increasingly, they’re greeted by press coverage and a large audience on social media.

Children mourn the death of a ten-year-old girl killed in crossfire between police and drug dealers in Rio, July 6 2017. Ricardo Moraes/Reuters

xx

People know what needs to happen first: the police must stop shooting. Then, to dismantle not just the gangs but also the gang mentality burgeoning among Rio’s police, the city must invest in intelligence.

The answer is not new, but it is globally tried and true: to reduce violence, reform the police.